Posted on May 12, 2023 by Brooke Crum

Lead Photo Example

UTSA and University of Texas at Austin researchers found that implementing culturally tailored interventions to prevent obesity in toddlers improved regulation of screen time and sleep but did not have a strong impact on dietary and physical activity behaviors at home.

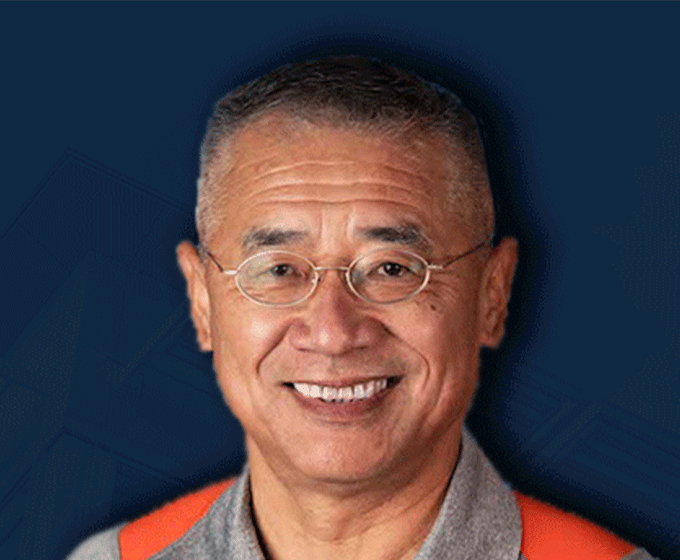

Zenong Yin, Loretta J. Lowak Clarke Distinguished Professor in Health and Kinesiology in the Department of Public Health at the UTSA College for Health, Community and Policy (HCAP), and Deborah Parra-Medina, inaugural director of the Latino Research Institute at UT Austin, co-led a multidisciplinary team of researchers. UTSA HCAP Associate Dean of Research and Professor Erica Sosa and Associate Professor of Nutrition and Dietetics Sarah Ullevig also contributed to the research.

Zenong Yin, Loretta J. Lowak Clarke Distinguished Professor in Health and Kinesiology in the Department of Public Health at the UTSA College for Health, Community and Policy (HCAP), and Deborah Parra-Medina, inaugural director of the Latino Research Institute at UT Austin, co-led a multidisciplinary team of researchers. UTSA HCAP Associate Dean of Research and Professor Erica Sosa and Associate Professor of Nutrition and Dietetics Sarah Ullevig also contributed to the research.

The researchers received a five-year, $3.1 million federal grant from the National Institutes of Health to investigate several strategies to prevent obesity in young children from low-income Latino families. They recently shared their findings in multiple conferences and research journals, including the International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity and Cambridge University Press’ Public Health Nutrition.

In partnership with Parent/Child Incorporated and Family Service Association of San Antonio, Yin and colleagues evaluated “¡Míranos! Look at Us, We are Healthy! (¡Míranos!)”, a multifaceted obesity prevention intervention designed to promote healthy growth in preschool-aged children enrolled in Head Start, a federal early education program for low-income families.

More than 491 three-year-olds enrolled in 12 San Antonio Head Start centers participated in the study. Almost 17% of the children in the study had obesity, defined as body mass index over 95th percentile for their age and sex, while nationally 12.7% of young children were obese.

Head Start centers were randomly assigned to one of three study groups: one that used intervention strategies at the center to improve healthy behaviors, one that used intervention strategies at both the center and at home, and a control group.

The researchers hypothesized that compared to children in the control group, children in the two study groups would gain less weight and have significantly higher levels of physical activity, sleep duration and fruit and vegetable consumption, and gross motor development as well as lower levels of screen time and consumption of added sugar and sugar-sweetened beverages immediately following the eight-month intervention and one year later.

The COVID-19 pandemic interrupted the researchers’ study in 2020 and 2021, so their analysis includes data collected from August 2018 to May 2020.

The results of the ¡Míranos! study found that children who received interventions both at home and at their Head Start center and children who received interventions only at their center demonstrated higher levels of gross motor development and higher levels of sleep duration as well as lower levels of screen time after eight months than the children in the control group.

Children received both the center and home intervention also gained less weight than children in the control group. Examples of intervention strategies used at Head Start centers include exposing children to new foods, providing more fruits and vegetables at meal times and more time for physical activity, health contests and an enhanced gross motor skills program. Intervention strategies used at home include parent education on obesity prevention, family health challenges, and home visits and goal-setting with Head Start staff to reinforce parent education.

However, the study results showed that the intervention strategies used had limited impact on children’s physical activity and healthy eating habits, which would require enactment of updated physical activity policies at the centers and investment in neighborhood resources to increase opportunities for physical activity and healthy eating where children live.

“The findings from this study support the role of parent education and training in changing young children’s health behaviors,” the researchers wrote in the International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity. “However, future studies should investigate equity-related contextual factors that either enhance or mitigate the impact of obesity prevention initiatives in health-disparity populations.”

In an effort to extend the ¡Míranos! study findings, the researchers partnered with the United Migrant Opportunity Services (UMOS), which administers the Migrant and Seasonal Health Start Programs (MSHSP) in four states, including 20 sites in the Lower Rio Grande Valley, Texas. They will adapt, implement and evaluate an obesity prevention intervention tailored to address the unique challenges of migrant and seasonal agricultural workers and their families, such as unstable income, long work hours, family mobility and access to healthy foods.

Yin said this research is important because of the high prevalence of obesity in young children from migrant and seasonal agricultural worker families. A needs assessment found that 24% of preschool children in UMOS’s 20 Head Start Centers met criteria for obesity, and these families face many obstacles to adopting healthy behaviors, including low family income, cultural and linguistic barriers and financial hardships that come with seasonal work.

“Addressing the obesity disparity among migrant and seasonal agriculture worker families requires an equity-oriented approach, as well as solutions that will help with the specific problems faced by this population,” Yin said. “Currently, there is little research on childhood obesity prevention for children of migrant and seasonal agriculture worker families.”

The researchers conducted a pilot program in fall 2022 at one UMOS’s Head Start center and just finished another pilot in another center this spring to make sure the ¡Míranos! program they created in San Antonio was feasible for MSHSP. In addition, they plan to test strategies to reduce inequitable access to resources that improve healthy behaviors, such as increased opportunities for physical activity at the center, access to and ability to purchase healthy foods, and availability of safe play spaces.