Posted on September 7, 2020 by Amanda Cerreto

This article originally appeared in the San Antonio Express-News , written by vtdavis@express-news.net

Krizia Ramirez Franklin is a graduate of UTSA, earning dual degrees in Public Administration and Criminology and Criminal Justice. She is a current student in the Master of Social Work program.

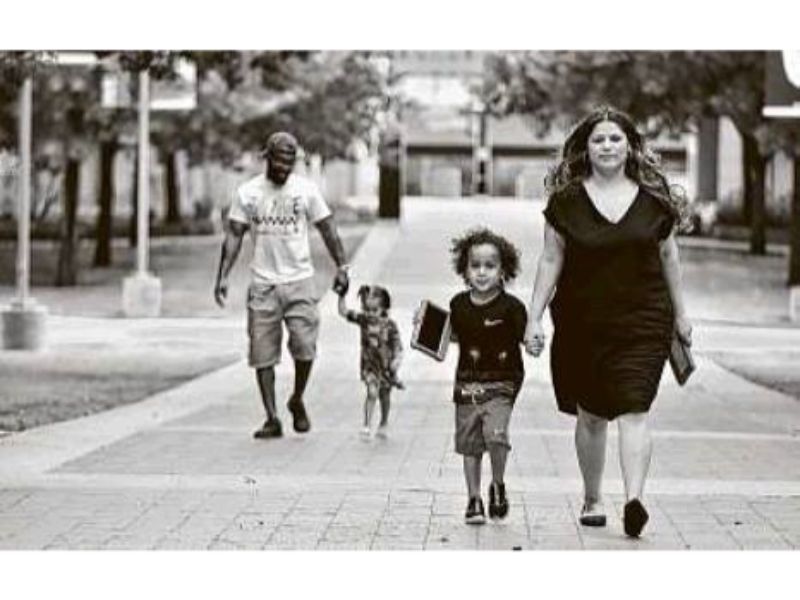

Photo by Robin Jerstad

Krizia Ramirez Franklin is a vocal advocate for children in foster care, a system she knows all too well.

She was 2 years old when she was first placed in temporary foster care because of her mother's substance abuse. Her father was in and out of their lives.

As her family grew, she was repeatedly separated from her six siblings who were scattered at different homes. By the time she was 14, she had lived in more than 50 foster homes in Texas, Illinois and Minnesota.

"You kind of feel like a travel bag," Franklin, 29, said. "It was a very lonely experience."

For the past 13 years, Franklin has spoken about her years in foster care, a moving story of sacrifice and resiliency, at state and national forums. As a member of the Texas Department of Family and Protective Services Council, she has toured shelters to see services provided to foster youth and represented Texas with the National Youth in Transition Database in Washington, D.C.

At the state capital, Franklin collaborated with Peggy Eighmy, wife of University of Texas at San Antonio President Taylor Eighmy, and with Child Advocates San Antonio and the Alamo Community College District to promote the importance of foster care youth obtaining a college degree.

In 2019, legislators approved $3.5 million for the Bexar County Fostering Education Success Pilot program that provides current and former foster and adopted youth the opportunity to succeed with resources dedicated solely to them.

And she's a volunteer program coordinator for Family Tapestry's Cultivating Learning In Middle School and Beyond program, a pre-college initiative. Family Tapestry is a division of The Children's Shelter, which provides community-based care for children removed from their homes by Child Protective Services.

“This is a free will, we-guide-you program and is foster-youth driven,” Franklin said. “We're empowering them through the Learning Independent Fosters Empowerment program and preparing them for what they have to face in the real world.”

Franklin said being in foster care for 16 years was like holding “a flashlight (and) trying to navigate through a dark tunnel.”

Originally from Eagle Pass on the Texas-Mexico border, she was 10 years old when a judge terminated her parents' legal rights after she had spent years in and out of foster care.

Four of the seven siblings were adopted by relatives; the others, including Franklin, spent the rest of their childhood in foster care, eventually aging out.

Franklin said she endured physical, emotional and verbal abuse at various times during her time in foster care that resulted in her rebelling and acting out her frustrations. But she did have angels in the system and foster homes who looked out for her, she said.

Among those angels were Mike and Debbie Briseño, her final foster parents. She remembers being taken to their home in rural Somerset late one night. The Briseños welcomed her into their mobile home where they cared for 11 other children. Later, the couple bought a house in Devine to accommodate the large brood.

Franklin said at first she was scared of the youth with varying attitudes. But she said the Briseños helped her find stability in a family that was rich with love and compassion.

Mike Briseño became the father figure she never had, someone who understood her years of pain. Debbie Briseño offered structure, discipline and held her to standards she knew the teen could reach. In the summer, she drove the high school student to San Antonio College and Palo Alto College for college credit classes.

When an episode of juvenile delinquency resulted in a court appearance, the couple told the judge they wanted her home.

“I knew those people loved me and that's when I changed my ways,” she said. “This family loves me. I can't let them down and I can't let me down.”

Franklin graduated from high school with honors and 33 college credits. In 2009, she aged out of the foster system at 18 and stayed in San Antonio, where she was attending UTSA. She volunteered with nonprofits and attended leadership conferences.

She didn't want to become a statistic, homeless, on drugs like some of her friends.

She graduated in two years with her first bachelor's in criminal justice, followed by a bachelor's in public administration.

Earlier in her young life, Franklin had met education specialist Norma Davila, known as “Mama Norma,” soon to be another one of her angels.

The two recall how they first met. Davila, 64, was giving a presentation on college financial aid to a group of foster youth, many who acted as if they wanted to be somewhere else. Not Franklin, then 16. She kept interrupting Davila, peppering her with questions and comments. The education specialist kept her cool.

Davila said Franklin's saving grace was she wouldn't take no got an answer.

“She knew she wanted to go to college and make an impact on the world,” said Davila, who has worked with foster youth for 25 years. “She was being stubborn, but that's one of her strong points.”

The pair have remained close.

Franklin is now a mother herself and finds her life fulfilling. In addition to all her volunteer activities, she works at San Antonio College as a student care advocate. She's grateful for the opportunity to fight for foster youth.

The thought of her children, M. J., 4, and Melody, 2, one day appreciating her overcoming struggles and taking foster youth issues to heart keeps her going. Her long-term goal is to become a family law attorney and start a nonprofit organization.

Tattooed below her left shoulder blade are the words “Foster Kid,” a term she wears with pride.

“I will forever be a foster kid,” she said. “I had to take that word back and despite what I've gone through, look at where I am at now. I never want to forget where I came from.”